When I was a kid, the computers at school were in the computer lab. You could go there and learn to code with a moving turtle, or play Oregon Trail (you’re dead! Dysentery … again).

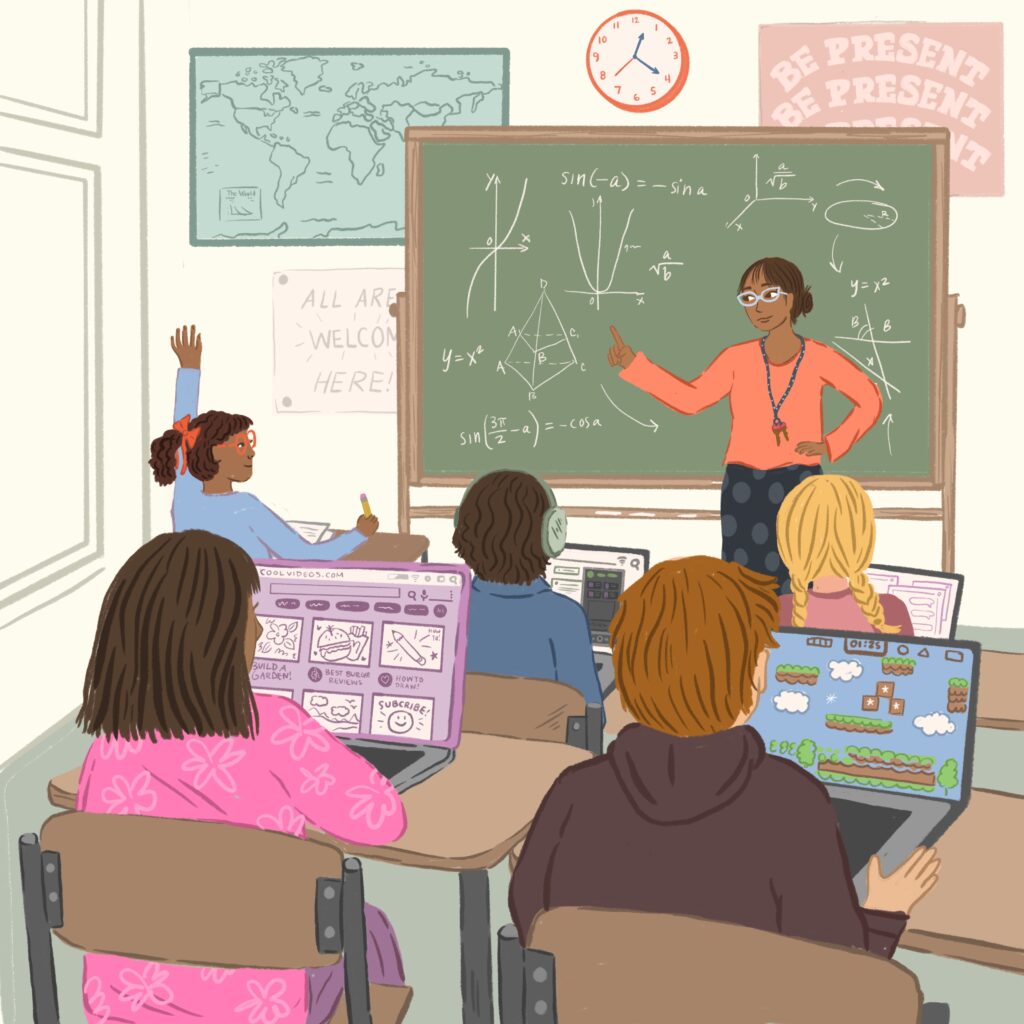

Fast-forward to the current moment, and your kids probably use computers at school all the time. Screens have become a ubiquitous part of classroom life. Is this a good thing?

Today is the first of two episodes on kids, screens, and schools. I’m talking to Jessica Grose from the New York Times, who writes on parenting and recently ran a survey of parents about their kids’ screen usage. Her goal with the survey was crowdsourced data to understand, basically, how much are kids actually using screens? And do their parents think it’s good for them?

Here are three highlights from the conversation:

How much time are kids spending on screens in school?

But I was like, “I should know how much time they’re spending on screens when they’re in school. And I also want to know how much time the average American child is spending on screens in school.” And so I started to look into the research.

And the short answer is, we have no idea, because there is so much variation. Not even district to district, state to state — we’re talking classroom to classroom. So an English teacher in Room 301 might be using screens entirely differently than the chemistry teacher in Room 302.

And I felt like the data that we did have was not particularly granular. And I feel like with a topic like this, the devil really is in the details. And so I wanted to hear from teachers and parents, “How much time and in what ways is tech being used in your children’s classrooms?” And there’s so many different ways it’s being used, too, so I wanted to get really granular information on that. You know? You have the Promethean boards, the whiteboards, the screen whiteboards. You have individual Chromebooks and iPads that are, honestly, more ubiquitous than I thought before I embarked on this project. And then you have apps; you have all different apps.

And again, we’re going to come back to this theme of lack of research. I talked to researchers at Harvard’s Graduate School of Education who had done a study on educational apps. And they said that when they did a review of the literature, there were only 36 studies. There are hundreds of thousands of apps billed as educational on any app store. And especially the way that education has really been remade in the past 10 to 15 years, it’s kind of incredible that there’s not more research.

How is screen use impacting how kids learn?

And so this was something that I had been hearing from college professors for a long time. And then it started creeping down, in terms of the stories that I had been hearing about the lack of attention, the lack of ability to concentrate, the lack of ability to do any work that required any kind of longevity and prolonged attention. And I think — people might disagree — I think that’s an important skill to have.

And I think that anything that is working against that skill, we need to think about, we need to talk about, but I also think that we all, as a society, have got into a narrative, led by tech companies, that more tech is better. That the higher tech that you get, anything, you will have an improved experience.

There’s little things around the edges that some things can improve a little. And especially for kids who have learning differences — dyslexia was one thing that really has been improved by tech — so I don’t mean to say it’s all bad. Nothing is all bad or all good. But I think overall, there just has been very little scrutiny into something that has been a massive shift in the way kids learn in the past, let’s say, two decades.

How can we implement better policies around screens in schools?

So somehow, I can imagine for schools, for parents, etcetera, getting to something that is a balance could feel almost impossible, right? That maybe there’s really only: go back to writing or just let it go like it is, neither of which seems like a great current solution.

But again, it’s not going to be a one-size-fits-all. I feel like you run into this often with the subjects you cover, that blanket recommendations are almost never useful. And so I think that just having those frameworks of “Is it useful? Is it necessary? Is it good?” is a place to start.

Full transcript

This transcript was automatically generated and may contain small errors.

I ended up getting my kid a phone, specifically because she needed a bird app for school. It was an app that recorded songs of birds and told you what kind of bird it was. So, as parents it feels like we’re stuck between a place where our kids are using technology all the time and they need technology all the time. And, yet, we’re being told to be afraid of it. And it’s so far outside our own experiences, it’s hard to look back and say, “Oh. Well, here’s what worked for me,” because we’re not actually going back to the world of Oregon Trail any time soon.

With all that as background, I want to dive into the questions of kids and technology. And this episode is the first of two conversations about what it means for kids to have access to technology, what digital hygiene looks like, and, specifically, how do we think about devices in schools? Both of my guests have conducted extensive surveys into these issues, coming at them from different angles, from different kinds of expertise, but ultimately trying to get at these same core questions, “How can kids live in the modern world, as good digital citizens? How can we help them navigate this world, one that we didn’t ourselves grow up in? And how do we put together our fear that technology might be going too fast, there might be too much of it, with the recognition that it’s here to stay and somehow our kids need to learn how to coexist with computers, with phones, with the technology that’s out in the world?”

My first conversation today is with Jessica Grose. Jess is New York Times reporter who covers family and education issues. And I asked her to come talk because she did a series, reporting on a survey about the use of technology in schools. So, she, like many of us, got curious about how exactly kids are using tech in schools. And she couldn’t find any detailed data on that question, so she went out and asked readers, “How are your kids using technology in schools?” And she came back with some reports, “How much time are kids on technology? How are they using it? What are the rules, generally, about phones in schools?”

In this conversation, Jess and I talk about what she learned from her survey of parents. We also talk a little more generally about, “What’s the role of technology companies in kid’s schools? How can we help kids enjoy the benefits of computers and screens and the internet, without the constant distractions that often come along with them?” And we also talk about positive effects of screens, particularly for kids with learning differences.

Part of what makes the whole parenting in the face of school technology hard is it can be actually pretty challenging to understand what is going on at school, with our kids, all day? Most of what I get at the end of the day is, “It was fine.” And what’s really valuable here about Jess’s reporting is it gives us a very clear picture of what kids are actually doing on screens in schools. And let’s think about, “Which of these things are valuable? And which of these things might we like to replace? After the break, Jessica Grose.

But I was like, “I should know how much time they’re spending on screens when they’re in school. And I also want to know how much time the average American child is spending screens in school.” And so, I started to look into the research. And the short answers is, we have no idea, because there is so much variation, not even district-to-district, state-to-state. We’re talking classroom-to-classroom. So, and English teach in Room 301 might be using screens entirely differently than the chemistry teacher in room 302.

And I felt like the data that we did have was not particularly granular. And I feel like with a topic like this, the Devil really is in the details. And so, I wanted to hear from teachers and parents, “How much time and in what ways is tech being used in your children’s classrooms?” And there’s so many different ways it’s being used, too, so I wanted to get really granular information on that. You know? You have the Promethean boards, the whiteboards, the screen whiteboards. You have individual Chromebooks and iPads that are, honestly, more ubiquitous than I thought before I embarked on this project. And then you have apps, you have all different apps.

And, just again, we’re going to come back to this theme of lack of research. I talked to researchers at Harvard’s Graduate School of Education, who had done a study on educational apps. And they said that when they did a review of the literature, there were only 36 studies. There are hundreds of thousands of apps built as educational on any app store.

Then, you’re seeing YouTube is available on Chromebooks, many Chromebooks. And some schools don’t… There are a lot of settings, so this isn’t… That’s the other thing, this is hard, this is a very complicated problem. There’s lots of settings, there’s lots of tools. And not all schools and school administrators are well-trained in how to use the tools that they’re already using. And so, one thing that came up a lot was Chromebooks.

So, and then, there were teachers who said, “When I can do those sorts of things more quickly, then we can get into more complex discussions and more complex kinds of learning, more quickly.” So, I talked to a high school English teacher who said, “You know? Because they can look up vocabulary words so easily, now my vocabulary tests are more sophisticated ways of usage, ways of using these vocabulary words in a sentence. And I even allow an open-book test, but the actual mental work to do that quiz is perhaps a little more challenging, because you’re having to think about nuances, that before you were just memorizing the vocabulary words.” So, again, there are ways of using it. I think it just always needs to be really thoughtful. And that was ultimately one of my big takeaways was that in 2020 and 2021, because remote learning-

So, I think that there’s this idea that if we just digitized everything it would be cheaper and we wouldn’t have to pay for textbooks. It’s a, at best, a wash, because those Chromebooks… Some teacher wrote in and was like, “There’s one eighth-grader who we’ve had to give four new replacements of various things.” You know? It’s just like the expense of that, the ecological damage of getting rid of all of these laptops that become obsolete, pretty quickly. So, it’s just like, “Let’s not.” The electricity use, all of that. So, it’s like, “Yeah, we have fewer photocopies.” Okay.

I mean, that’s something that I have not allowed my middle-schooler to have a cellphone. And part of the reason why is because when she’s hanging out with her friends, I went them to be hanging out and not all gathered around a screen together, which, obviously, they still definitely do, but I would try to minimize that, especially when they are out and about in the neighborhood. And, even something like doodling, I think doodling is more generative than sitting and watching a clip from A Clockwork Orange, when you are supposed to be in the middle of your English class, which is an actual… Although, listen, A Clockwork Orange is a great movie, I’m not going to lie.

And even, possibly, and this is even more extreme, having time limits, saying, “An hour a day. We are striving to have the kids, one out of eight hours on screen, and that’s it.” Again, it’s like the needs of every school are so different, and so it is tough to say that, but just having them up all of the time, I can’t justify it. I don’t think that there is any reason for it and I think it is a net negative, so that’s what I would say.

Community Guidelines

Log in

Seems like a lot of opinion and little to no data

I’m not sure there’s anything wrong with writing a long essay in longhand. That’s what we all did back in the 90s. You can always type it up later.

I’m also not convinced we “need” to learn tech like google groups (which I barely use myself as an adult). I had only a typewriter until college. When I started college, I walked into a computer lab and asked another student how to type an essay on the computer. She taught me, and I was off and running with MS Word. You can always learn tech when you need to. No need to learn it just for the sake of learning.

Also, I did laugh a bit about the Clockwork Orange conversation. I actually DID watch part of it in a high school class, with the teacher. Our English class did a unit on film, analyzing them as literature. I’m for that kind of tech in school: the whole class viewing something together, guided by the teacher. Hey, it’s a great movie.